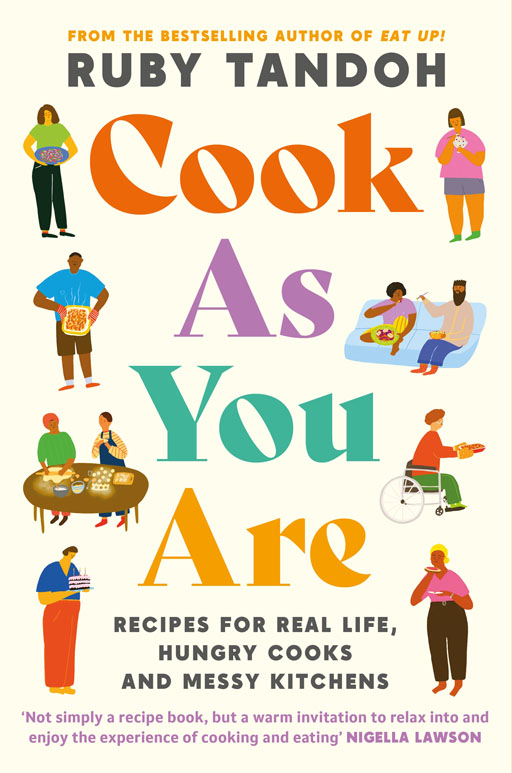

After her latest book, Eat Up, which celebrated the fun and pleasure of food, Ruby Tandoh is back with Cook as You Are, a cookbook unlike any other. We talk with the British food writer about the idea behind the book, what it means to ‘meet our hungers’, and the comforting goodness of gnocchi.

With Cook as You Are, you set out to create a cookbook that is accessible, thoughtful and inclusive – that’s an admirable goal for any writer. Can you describe your approach that enables you to achieve all of these things at once?

There can be a lot of pride wrapped up in cookbooks: as an author, you want people to follow your lead, to trust in your judgement and to follow your instructions. But – when writing Cook as You Are, I knew I had to set ego aside and take a more flexible approach. Instead of just mindlessly following my lead, I wanted readers to feel empowered to adapt recipes to their taste, situation and budget. That means I had to set aside any preciousness I might have about my recipes and encourage people to cook as they are – not as I am – in order to find real confidence in the kitchen.

How do you make sure the book reaches audiences beyond the usual foodie circles? Is there a particular way you appeal to the average reader?

I’d say the abundance of variations and substitutions (all of which have been tried and tested by me) help to make this book a really valuable resource for any cook, no matter your budget, skill or the size of your kitchen. These adaptations are listed in most of the recipes, so whether you need help using up leftovers or want tips for how to make a recipe more hands-off, I’ve got you covered. Flexibility is the name of the game here, and it’s that ability to work with what you’ve got that is, I think, the mark of a good cook.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

You invite readers to step into their messy kitchens and cook a meal, even if they have limited time and resources. But some people might wonder why they should make the effort, when they could so conveniently reach for a ready-made meal. What would you tell them?

Honestly I like to avoid being moralistic about these things! If you really do hate cooking, through and through, and you feel happier getting a ready meal, I think that’s fine. If you have a disability that makes cooking exhausting, use pre-prepared ingredients and dishes. I don’t believe that everyone has to cook!

However, I do also think that some people have a huge amount of anxiety about being ‘good enough’ in the kitchen, and that anxiety can be immobilising. If the thing holding you back really just boils down to nervousness, or a mental block, or even stubbornness, it’s well worth giving cooking a go with a few simple, low-fuss recipes. If after trying it you’re still not sold, convenience foods will still be there, and still be delicious.

I had to set aside any preciousness I might have about my recipes and encourage people to cook as they are – not as I am – in order to find real confidence in the kitchen.

Humans are creatures of habit, and many of us find it scary to adapt our usual go-to recipes or experiment in the kitchen. Can you give some examples of how the book encourages readers to step out of their comfort zones?

That’s hard to say because of course everyone’s comfort zone is different, isn’t it? For some people, the day-to-day will be bowls of dal, while for others it’ll be pasta, or fufu, or beans on toast. It felt important to reflect that diversity in this book: to resist assuming that everyone will be singing from the same culinary hymnbook. So there’s a real breadth of ingredients and cuisines in these recipes, from chilli crisp oil to harissa, pierogi to omo tuo. There’s bound to be something that’s new to you, but exactly what that is will depend on which foods you know and love already.

You deliberately opted for illustrations rather than photos. Can you tell us a bit more about why you went this route?

It felt really important, especially considering the title of the book, to resist the urge to present these recipes in glossy photos. When you photograph a cookbook in a studio kitchen, with rented props, with a food stylist helping to make the food otherworldly beautiful and a photographer tweaking the light just so, what you end up with is a vision of that recipe that isn’t particularly realistic. I didn’t want readers chasing the impossible in trying to recreate those photos, so I decided to follow the lead of some cookbooks I love (Nigella Lawson’s How to Eat, Nigel Slater’s Real Fast Food, Mollie Katzen’s The Moosewood Cookbook) and do away with photos altogether. The illustrations that Sinae Park has created are perfect, I think, because they show such a range of kitchens and cooks, so that readers can see themselves represented in the pages of this book, no matter who they are.

The illustrations that Sinae Park has created are perfect, I think, because they show such a range of kitchens and cooks, so that readers can see themselves represented in the pages of this book, no matter who they are.

You make a case for using canned or frozen ingredients, which are generally frowned upon by the ‘foodie police’. Do you think the pandemic has influenced the way we look at cooking with staple pantry items?

I think it has, to a degree. So many people have found their relationship with food changed over recent months, whether that’s having less money to spend on food, having to turn to tinned and long-life foods for fear of shortages, or finding themselves cooking more if they’re working from home. These changes have, for some, been really difficult, but I think they’ve also built a little more empathy among others. There’s an awareness that the things we took for granted may not last forever, and against that backdrop, it seems ridiculous to crusade against, for example, long-life milk when so much life-or-death stuff is happening around us.

What are some of your own comfort food favourites from the book?

I love gnocchi: the weight and heft of those fat, soothing little dumplings. So the gnocchi with chilli crisp oil, capers and parmesan is an absolute favourite of mine. It’s packed with umami goodness and although it is, I realise, an unconventional combination of flavours, it’s one of the most-cooked and best-loved recipes in the book so far! I’m very proud of that recipe.

Other favourites include the puff-puff (West African drop doughnuts, which are light as a feather) and the extremely simple soured cream vanilla cake, which forms the foundations of most of the celebration and birthday cakes I bake.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Let’s say you’re cooking a dish and sampling it, but it’s just ‘meh.’ In general, what are the go-to ingredients you reach for to elevate a dish?

Often it’s as simple as there not being enough salt in a dish, but you don’t have to just reach for the salt shaker to remedy this. There are ways of adding salt that also add savouriness, tang or spice, and these are well worth exploring if your dish just feels ‘flat’. Miso paste, olives, soy sauce, anchovies, preserved lemons, fish sauce, chilli bean paste, capers, Maggi sauce: these are all shortcuts to flavour and good seasoning, if you use them right.

If it’s not salt you’re missing, often it’s a mixture of acidity (lemon juice, vinegar, pickles, tomatoes, sour mango, tamarind, wholegrain mustard) and sweetness (honey, sugar, tomato puree, dried fruits, dairy) that you’re missing. Get the salt, sweetness and acidity in perfect balance, and your cooking will come alive.

In your book you speak of “meeting our hungers here and now, as we are”. What does this mean for you?

This is about not constantly judging, reprimanding and berating yourself for not being a perfect cook or eater. There’s a really strong aspirational bent in our food world: the desire to improve yourself, your reputation, your worldliness or your social class through the foods you eat. But this (as well as being unrealistic) means we stop seeing the value in our appetites as they are, right now. I think there’s huge value in just relaxing for a moment and seeing where your hunger might take you.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.