Few, if any, designers can claim such a complete mastery of both form and function as Achille Castiglioni. Beyond that, even fewer designers can claim to have created iconic designs that are not just staples of the world’s most revered design museums, but are also so universally cherished that – as in the case of his iconic Arco Lamp – they were once said to be found in 10% of all Italian homes.

This quality speaks to the enduring appeal of the Milanese maestro. The allure of other similarly stellar design names tends to fluctuate with the whims of current design trends. The value of Castiglioni’s work, however, is more constant and sets his work apart from the latest fads. The reason is simple: where some designers indulge in design for its own sake, Castiglioni remained committed to design that delivered, his works adding meaning and value to the spaces they exist in.

IL MAESTRO

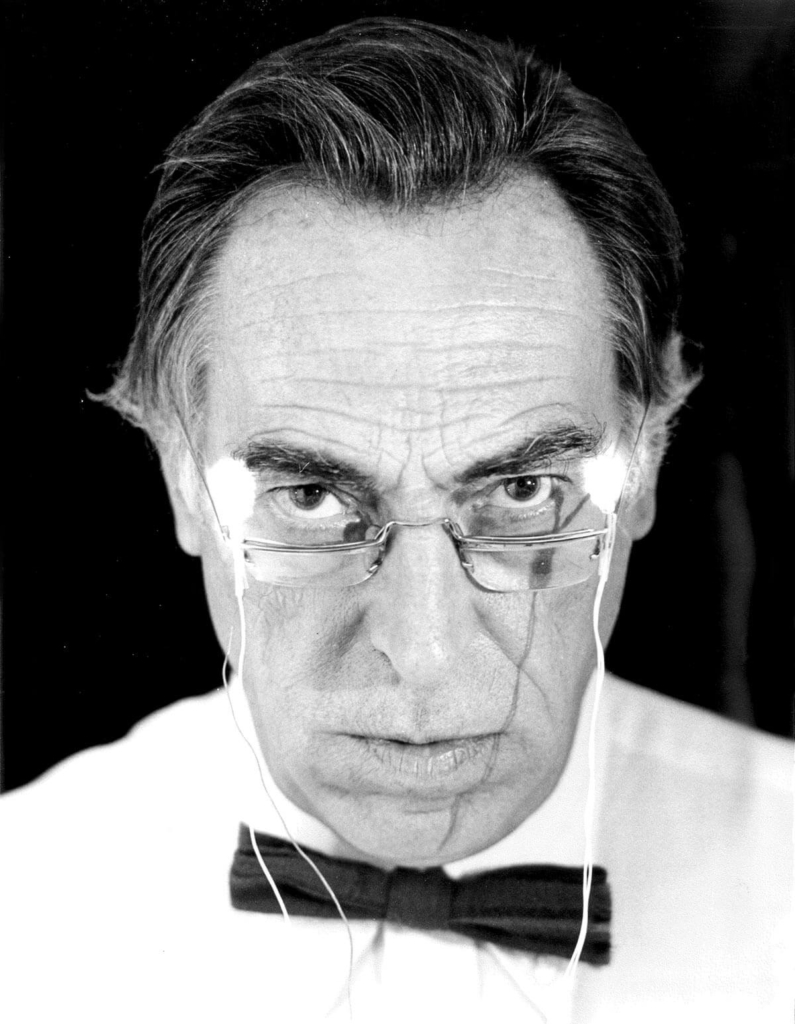

It does not take long to realise how different Achille Castiglioni was. That was just as much the case when he was alive and restlessly trying to reshape the world around him as it is today, in our age of internet celebrity with people attracting millions of clicks for their often mundane and banal opinions.

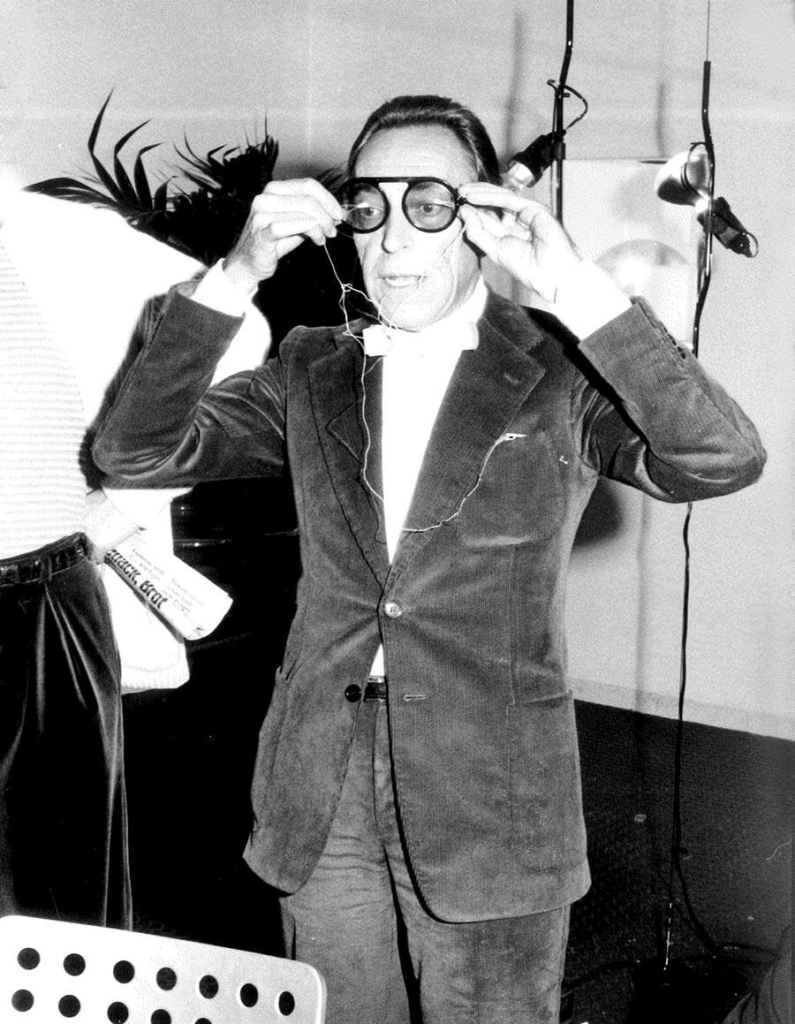

Even a quick glance at this archive footage available on YouTube shows the entertaining mayhem that ensues when the effervescent Castiglioni took to the stage of the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado back in 1989. There, in front of entrepreneurs and leading figures from the field of industrial design and architecture, this middle-aged designer did not stick to describing his creations in an orderly or predictable fashion. Instead, he dismantled and reassembled the entire stage around him. Amusing as it is, this is no court jester in a suit, this is a restless and inspired genius in full flow.

Today, Castiglioni is ranked among the most influential designers of the last century, whose works are so iconic as to be displayed in the permanent collections of the world’s most important museums, such as MoMA in New York or the Triennale di Milano. On top of an entire life studded with remarkable achievements, it was primarily his experimentation in lighting and the fruitful cooperation with the company FLOS that pushed the Castiglionis – Achille worked in tandem with his brother Pier Giacomo until the latter died in 1968 – to take the first steps in the design world and to bring into being such authentic artworks as the Luminator (1954), the innovative Toio (1962, made with a 300-watt car headlight) and, of course, the Arco Lamp (1962).

THE ANATOMY OF A DESIGN CLASSIC

The Arco Lamp is a model of usefulness and usability. A free-standing floor lamp, it is specifically designed to project light onto a table underneath. However, it is three simple components that give real substance to the concept: an arched, pivoting telescopic arm, whose curved line ends with a flower-like head supporting a lightbulb and providing both direct and indirect light, all of it counterbalanced by a 65kg block of Carrara marble as the base.

Nothing has been left to chance and nothing is superfluous: neither the curve of the stainless steel stem – which reaches out two metres from the base to the table, providing a range of motion for the swivelling lamp – nor the decision to opt for marble, as it was the most economic and space-saving way to give the lamp a heavy foundation. Even the off-centre hole in the base was planned to perform a key function, allowing two strong men to carry the base comfortably by running a broom handle or thin rolling pin through the hole. The inherent beauty of the product is almost inadvertent, where everything has been designed to perform a precise function. Castiglioni’s stubborn adherence to getting to the essential core of an object was probably one reason why the lamp is now protected by copyright, a prized distinction bestowed only on a few design objects having a “consolidated and permanent representative and evocative character”.

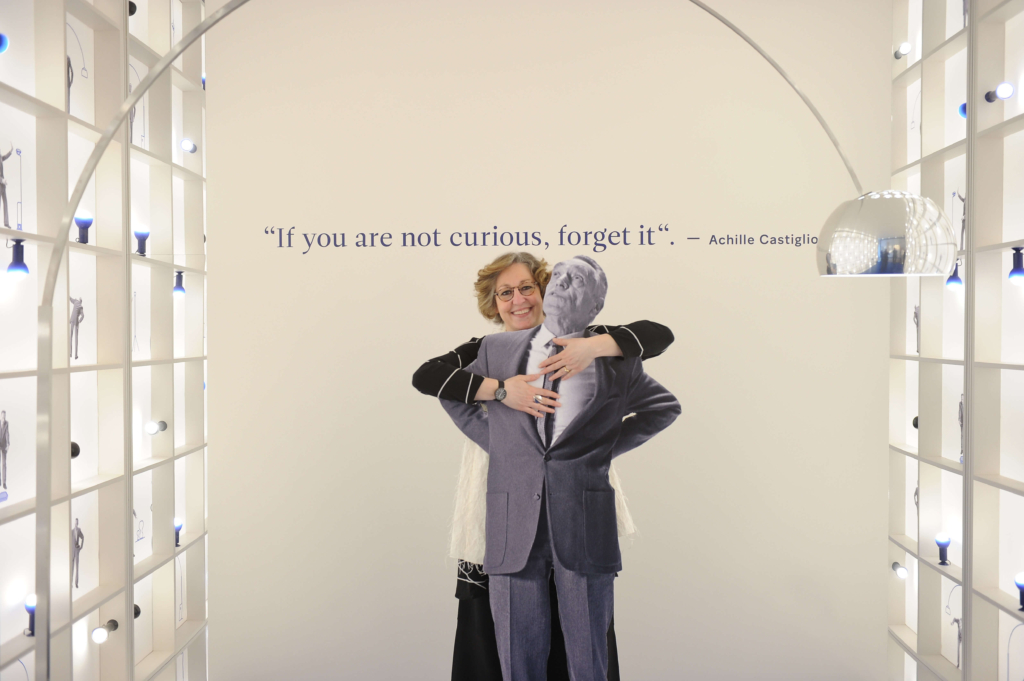

On the centenary of his birth, we spoke to Castiglioni’s youngest daughter, Giovanna, who today takes a leading role in Fondazione Castiglioni. Based in the designer’s former studio in Piazza Castello 27 in Milan, today the museum attracts thousands of visitors annually.

AMEX ESSENTIALS: What was the spark of inspiration behind the Arco Lamp?

GIOVANNA CASTIGLIONI: The street lamps on the sidewalks of Paris, with their curved poles bringing light to the streets. The Castiglioni brothers, both Pier Giacomo and Achille, literally fell in love with this concept and simply decided to move it into people’s houses. As luck would have it, they found the company Flos and its enlightened entrepreneur Sergio Gandini, who believed in this very bold project for those times. It was 1962.

On reflection, were they more visionary or reckless?

I would say a unique blend of both. Simply the fact of being able to look around and then firmly decide to grasp the nettle of radical change and shake up the interior of a house that had ceiling-fixed chandeliers back in the 1960s, was a pretty bold move. By designing this swivelling arc, they ensured the light still came from above, but – with a nod to rebellion – they deconstructed the classic chandelier common in bourgeois houses of that period.

As much as the Arco lamp was suitable to be placed over an armchair for ease of reading, your father was pretty keen to raise objections to this misuse of the lamp. Could you explain why?

Well, I try to make this point very clear with a little ‘learning by doing’ interlude during conferences, just as my father also used to do: I seat people on a sofa or an armchair by the Arco lamp – I always choose the tallest gentleman – and then ask them to suddenly stand up. It goes without saying that they bang their head against the lamp every time! All this to make it clear that the Arco lamp was deliberately designed to cast light on a table and to have enough space to move around it. There was a historical advertising photo showing a man sitting at a table and a woman passing between his chair and the Arco lamp.

Design should meet the needs of the audience, not the need of profit.

Precisely this fact struck me after watching the video of the Aspen conference in 1989, where a young woman contends with your father’s enthusiasm on the stage, while trying to keep up with the translation.

Well, that fantastic young woman is now the director of research and development at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York: Paola Antonelli, who back then was a young design student, working as Italian coordinator for the International Design Conference in Aspen.

On that occasion, she had been asked to be my father’s translator on stage. [Laughing] What a challenge for her! He spoke with a Milanese accent the whole time, and his back-and-forth on stage made the task even more demanding. However, the main reason for his restlessness was actually his innate shyness, certainly not any sense of glibness.

So he basically used objects to gain additional strength on the stage or in front of a camera?

Yes, exactly. He relied on objects as authentic lifesavers, and let them speak for themselves. During the guided tours for foreigners at the Castiglioni Foundation, I’ve almost always been told that one of the most beautiful things about my father are his gestures: everybody understood and still understands what he meant in his own way, as a very good actor performing in a silent movie. He didn’t like bragging about his inventions, but simply showing how he had realised them, like any enthusiastic kid would have done.

The manufacturer FLOS – and other great design companies – helped your father produce many designs, including the Arco Lamp. What was the relationship between him and such companies?

This is a very important question, because it precisely pinpoints what I think is missing nowadays: today, the designer is hired by the company as art director and defines the project requirements in advance. This somehow eradicates the creativity. My father would have never worked as art director, because he just did not want to give his own approach. He was always happy to discuss the project, to talk to the workers, to think together with the engineers, with the company manager – working with everyone in perfect harmony, as part of a team. In the 1960s, this was possible because the entrepreneur was an enlightened businessman, who picked the right architect, at the right time: it really was the golden age of design.

Could you illuminate the typical process in detail?

For example, the entrepreneur requested a bedside lamp or a cutlery set or a table service of a certain type, and Achille started creating models and test sets, which were themselves a force to be reckoned with – he presented more than 480 sets throughout his entire career. The set, basically the space, gave him the chance to test a chair or a lamp specifically made for that space. If the chair or lamp did not blend in, the company was happy to wade into the process and say what needed to be changed in order to finally manufacture it. There was an open-mindedness from the higher-ups, and not only in financial terms: all they wanted was to work with the designer, not to create a one-off product, but a serial product. They wanted art to be accessible to everyone.

Which is very different today, right?

I’m thinking about the marketing logic: today, companies launch a survey first, to see if customers prefer object X or Y, if one of the most in-demand colours this year is green or yellow. The problem is that in so doing, you will never truly satisfy all your customers. Castiglioni was sure that if the object works, it works for me, for you, for your children, but also for your grandmother. Function goes beyond fashion, marketing, style – all things that he did not like. That’s why, whenever there was a meeting with the marketing team, he always vanished.

There can be no beauty where there is no use.

Professionally speaking, what struck you the most about your father?

What caught me when I took over the studio was that he set up meetings with retailers, because whoever sells the item must know what they’re selling. Achille considered that to be even more important than basic marketing, because people count, and retails shops still sell! In the end, he said, when you take home a particular object or a piece of furniture, you know what you bought, you get attached to it, it keeps you company. People do have to buy design to use it, it is extremely expensive! If you buy a sofa, it’s because you want to flop down on it and if the cat sharpens its claws on it, well, it should be fine.

And the personal quality that you admired the most in your father?

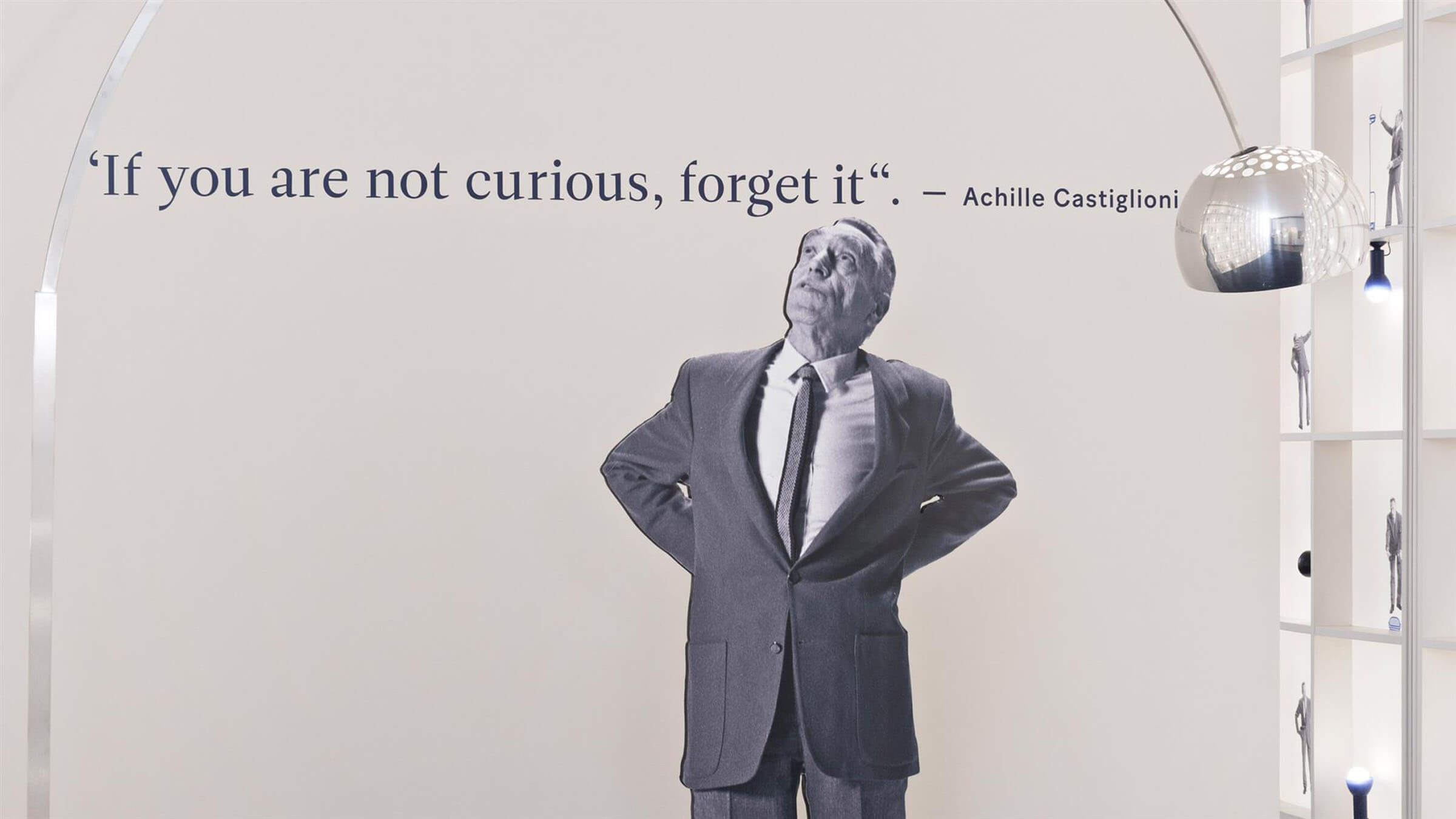

Undoubtedly his curiosity. One of his most famous quotes says: ‘If you’re not curious, forget about it. If you don’t care about others, what they do and how they work, then designing is not the job for you.’ This doesn’t only relate to curiosity – which allows you to pay attention to details, even anonymous details, in a world where we are bombarded by constant input – but also to the form-function dichotomy: as soon as you have an idea for an object that can improve everyone’s life in practical terms, the form will follow.

In your opinion, was your father aware that his creations would achieve a worldwide success?

No, he did not care at all: he won 8 Compasso D’Oro Awards, one of them honorary, plus thousands of other prizes, but the essence remains: he could not have cared less. He was certainly proud of them, of course, and he was flattered to get them, but this was no strong incentive to keep designing. Design was always a pleasure, not affected by performance anxiety. Maybe today we should stop for a moment to think and carry out projects we believe in, instead of realising only prototypes every year, without actually putting them into production.

Was there a difference between the public and the private Achille?

No, absolutely, it was just him, plain and simple, spontaneous and honest, with no filters. Every time someone came to visit him at the studio and rang the bell, he opened the door and said either ‘Look, I’m working, please come back later’ or ‘Come in, I’ve got two anonymous objects that I’ve just received, and I’m so happy to show them to you.’

The good thing is that he collected such a huge amount of items that we’re trying to sort day by day, especially this year with the centennial celebrations and all the exhibitions we planned. And we find that we get to know him better through them. We keep scanning his graphics and we worked on a special exhibition called 100×100 Achille, where we asked some of the most important designers today to think about an anonymous object they would have given my father as a present for his 100th birthday.

Are there any designs your father was particularly attached to?

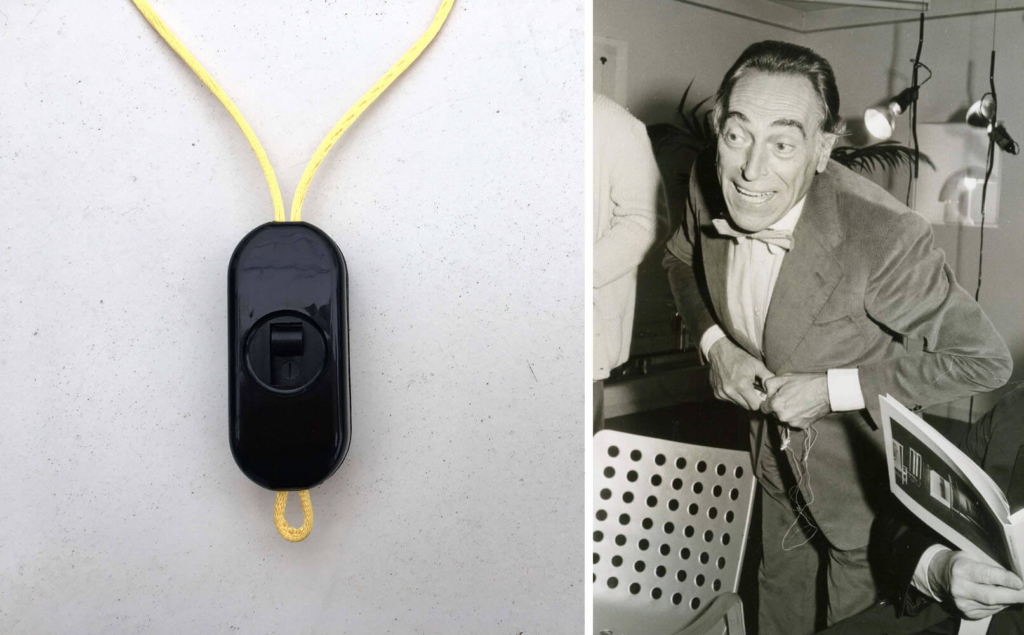

Yes, and it was also the one he was most proud of: the light switch he designed in 1968 for VLM, which cuts off the flow of electricity and can be applied to any kind of wire. Thanks to such an apparently trivial intuition, my father managed to be in every home in the world. Everyone owns a Castiglioni, but they aren’t even aware of it!

As Achille Castiglioni’s daughter, how did you deal with your father’s stardom? How was he at home?

He was a very thoughtful and active father, who never made his notoriety weigh upon me and my brothers. That’s also why I insisted on keeping the Foundation open, which was strongly supported by my mother, Irma, who wanted to metaphorically feed Achille to the people, so they could get access to his universe. The Foundation, which is also in danger of closing, is not a ‘cold’ museum, but a space with objects that you can touch, and that sweeps over you with the extraordinary power of daily life – first of all because you’re welcomed by a barking dog, my basset hound, Linea.

One is not born a genius. One builds up a career even thanks to the failures. If you talk to any architecture student, he tells you he’d like to become the new Philippe Starck, who gains even more admiration due to his great communication skills and versatility.

Who is taking care of the Castiglioni Foundation?

My brother Carlo and I, together with the historical collaborator Antonella Gornati, who worked together with my father for a long time. We took the baton, and we’ll keep working intensively on his archive, as well as planning activities for the continually curious visitors. 40 years of [design] history must count, and there is still so much to tell. Our hope is to carry on this story even when we are gone. As the future is built on strong foundations, we are here to provide it with this solid foundation. We tell the story so that others will be able to build the future.

Follow the Fondazione Castiglioni on Facebook and Instagram.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.