In any good story there is a climax: a moment in which the hero must give their all. Usually, the more that’s at stake for the protagonist, the more this part of the story captivates the attention of the audience. But no movie – and no story – can really convey how the protagonist felt as they were to face their biggest challenge. Usually, the hero is faced with a series of obstacles that they must overcome in order for them to grow before reaching that fateful moment. They’re invested in the quest with every fibre of their being, and they simply must make it. But how do they actually do it?

In books as well as in movies, the struggle is often glossed over; in fact, it is a common opinion in storytelling that the hero’s grind is not that interesting. We, the audience, want to see the protagonist complete the quest, beat their enemy and succeed; that’s what gives us satisfaction. But in doing so, we might fall into the pitfall of thinking that real life, too, can be so simple.

The sobering truth is that accomplishing anything of value involves constant commitment and several setbacks, usually over a long period of time. And nothing can make you accept that concept better than a mosaic class.

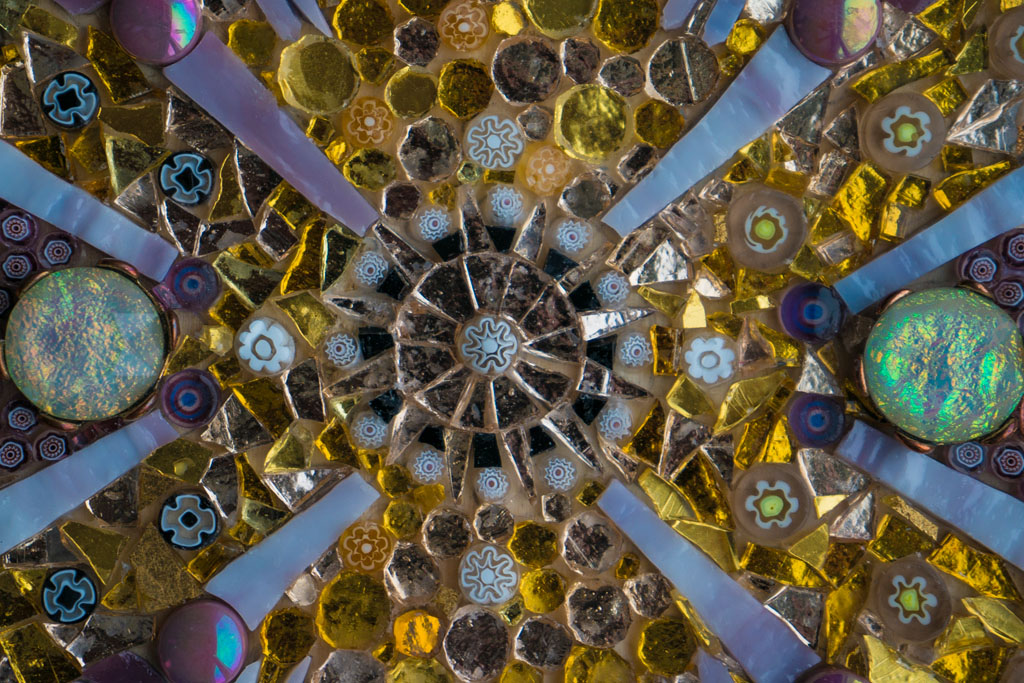

Putting together a complicated puzzle of your own design, including shaping every piece of it, can teach you a lot about the importance of doing the gritty work, accessing the deep well of patience needed in the process, and even accepting the need to let go. The good news, though, is that mosaic is a powerful way to train your creativity and problem-solving skills, and that with the right technique, even beginners can achieve beautiful results (spoiler alert: I did).

[Photo: Livia Formisani]

Choosing The Right Mosaic Method

Mosaics can be created by following two main techniques: direct and indirect. The direct method involves composing the image exactly as a puzzle: the artist is in control of every aspect from the very beginning, and the image is facing up. The indirect method, often used for floors and other large surfaces, consists of composing the design face-down, then transporting it (glued to a backing) to its destination.

Beginners will obtain the best results with the direct method. In fact, while mosaic-making is relatively straightforward to learn, I struggled with three aspects when I first started out: the size of the gap between the pieces, the choice of colours, and the actual composition. Practicing with the direct method is the best way to understand how to solve these challenges before tackling bigger projects.

After choosing the technique, it’s time to pick the materials. A good option, often seen in bathroom tiling, is glass. Mosaic glass tiles can be bought pre-cut in 2x2cm pieces (a great and easy option for kids, for example), or in bigger sheets which can then be cut into small pieces. These come in all colours and textures: stained, mirrored, gold and silver foil-backed, and many more. Should you opt for a sheet, glass-cutting tools are not difficult to use, though they require a little bit of practice (and safety glasses).

Aside from glass, mosaics are also usually made with stone, smalti, ceramic and porcelain – but most of these materials need to be cut with a hammer and hardie, which requires training and practice.

[Photos: Marleen Lacroix]

Designing And Cutting

Creative freedom brings a breath of fresh air into our structured lives, but the sheer number of possibilities can quickly become overwhelming – and that is true for every artistic pursuit.

This is why I decided to approach my mosaic class with an idea of what I wanted to reproduce: a detail from Van Gogh’s The Starry Night. I was glad I did, as when I first saw the many available shades of coloured glass, my mind started wandering about everything else I could do instead.

What convinced me was learning about the different glass-cutting tools, and what they can be used for. One of them, the wheeled glass nipper, seemed ideally suited for my enterprise. The tool – which cuts straight or curvy shapes – was perfect for creating rounded stripes that could vaguely (notice the emphasis) resemble some of Van Gogh’s strokes. In any case, if you are unsure what to do, let yourself be inspired by the beautiful materials. A specific colour or texture may powerfully trigger your imagination.

After choosing the most appropriate shades of colour, I started to cut the pieces. Working with the wheeled glass nipper at an angle gave me a weird feeling: I had control, and yet I didn’t. I could roughly choose the size and shape of the pieces, but the actual result was always going to be somewhat of a surprise. It felt liberating. “Even in mosaic, you can choose to go with the flow,” said my teacher, Marleen Lacroix of the Mosaic Lacroix school in Luxembourg.

[Photos: Marleen Lacroix]

How Do They Actually Do It?

I approached mosaic art thinking that it was a very structured, even mathematical form of art. And it can be, but it’s also a great way to train your creative muscles. Not only did I have to plan my design, choose the colours, and cut the pieces – I had to make them fit. And it might sound trivial, but the same piece looks completely different if used upside down, flipped or simply placed somewhere else. As the author of my project, the choice was completely up to me. And the way this exercise forced me to step up my problem-solving skills was fascinating to experience.

I had to constantly think outside the box, sometimes choosing lateral solutions, sometimes accepting and integrating mistakes I couldn’t fix. Always doubting whether everything I was doing would produce something lovely, and wondering if I was going to ruin everything by placing the next piece, by making the next move. And the problem was that the more I went on, the fonder I grew of my tiny piece of art, and the more attached I became.

The stakes were undoubtedly rising. How was I going to solve the next challenge? I simply had to wait and trust that I could find a solution. And piece by piece, doubt by doubt, I did it. To my greatest surprise, the end result looked spectacular to me.

In his 2011 book Do the Work, author Steven Pressfield wrote: “Fear doesn’t go away. The warrior and the artist live by the same code of necessity, which dictates that the battle must be fought anew every day.” As a writer, I can tell you that this is true. And maybe that’s how the hero actually manages to overcome their challenge: by fighting the same battle, with themselves and the world, regularly, relentlessly, by facing the same fear every day. Until that fateful moment arrives.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.