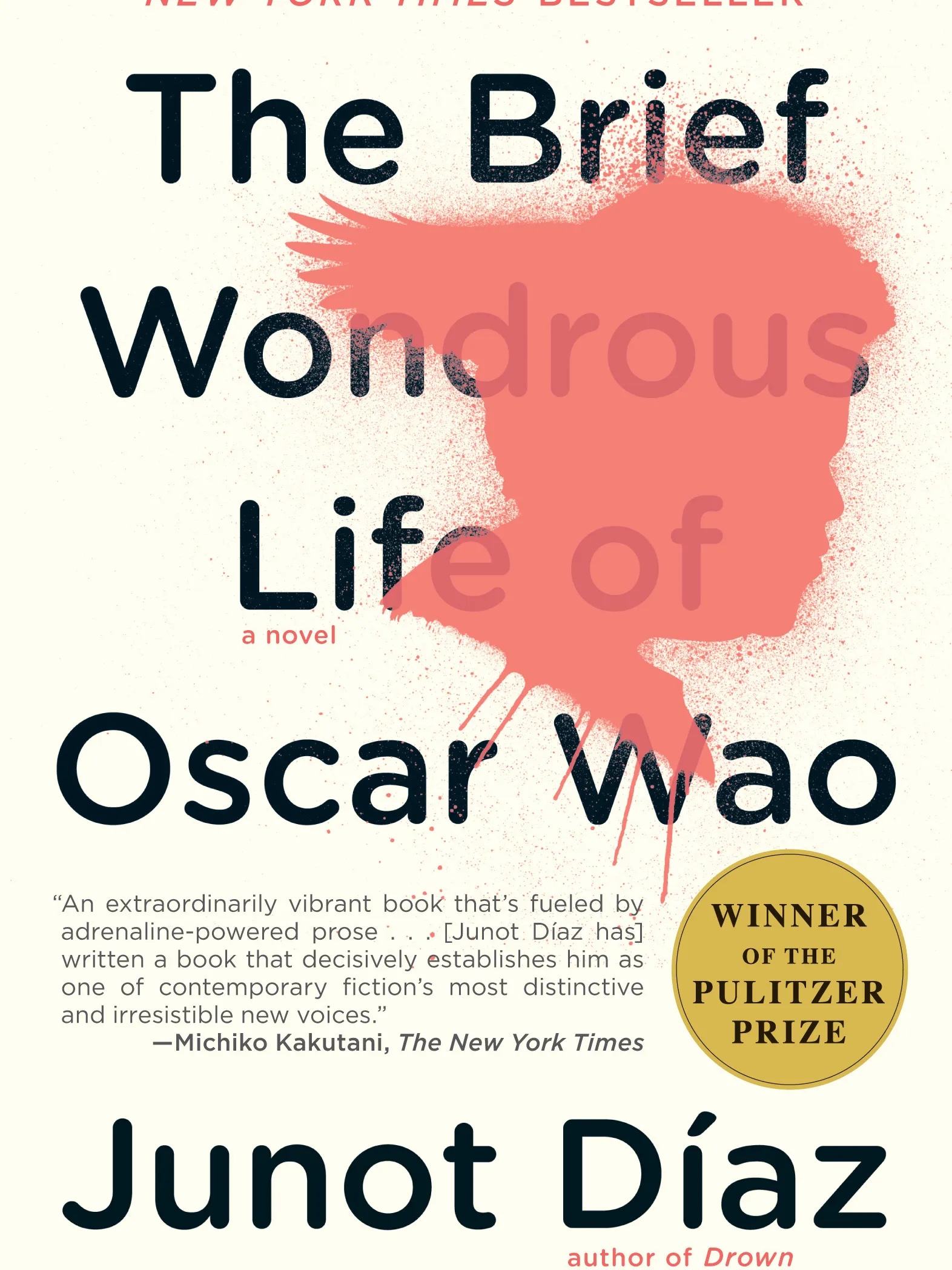

Junot Díaz has emerged as one of the heavyweights of the contemporary literary scene since the publication of his award-winning The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. A Pulitzer in his back pocket and millions of copies sold around the world, he’s often been deemed as one of his generation’s most virtuoso writers, and his characteristic use of language and code-switching are easily recognisable for bookworms and aficionados.

With a new book on the horizon, after a years-long publishing hiatus, Díaz spoke exclusively to American Express Esssentials about his thoughts on culture, the immigrant experience, the struggles of being a professional writer, and what he’s been doing for the past twenty years: teaching.

Are you writing anything that’s set to be published? Or are you writing just for yourself at the moment?

I mean, one hopes. I’ve been working on this novel for a while now, and I’m very close to getting done with the first half, which is the absolute hardest part of this book. I’m probably kidding myself, you know? How easy it is. I think talking about a book before it’s done is like talking about a relationship after a blind date. It’s absurd, you never know what the hell is gonna happen next, but so far it feels like it’s about halfway done.

Could you tell me what it’s about, or is it confidential?

In some ways it’s so absurd and ridiculous that it doesn’t make any difference. I could talk about it, and people would just look at me like, “Yo, you definitely are very bored.” I saw Black Panther and, I guess because I come from a country where the majority of the people who run the country are of African descent, for me the fantasy of it was not that there’s this hidden polity in the middle of Africa that has science-fictional powers. For me, the idea would be that we would have an incredible amount of power and we would be good. So this is a book about a Caribbean Wakanda, except instead of being these benevolent, kind, wonderful superheroes, they’re in fact horrifyingly just human, which is to say real oppressive.

Is it safe to say that it would be your first sci-fi novel?

Yeah, I guess so. I’m not sure anyone who reads science fiction would want to read this, ‘cause in some ways it doesn’t give any of the standard bells and whistles. The main narrator, instead of being a sort of heroic character, is more of an absolute chickenshit coward, which is the only way that he keeps surviving. Throughout the book, everybody else keeps being slaughtered and murdered and imprisoned, but he’s just this incredible, weak-willed coward, so he’s an excellent survivor.

When you write, do you find yourself struggling to find the right words or do they just come to you?

Of course, my God, sentences are a puzzle. Some sentences, you figure out the puzzle quickly. Some… There was a sentence this morning I fixed, and it had been more than six months trying to figure it out, and finally I broke it. It was back on page 20, I’m on page 400, but I would keep going back to that sentence and looking at it.

So yes, but certainly there’s times when what tends to slow me down as a writer has more to do with constructing the correct silence for the character or the narrator. Often, what powers my books is the unsaid. The unutterable. If I don’t get the relationship between what the narrator or the text is saying, and what it’s holding back, and usually holding back in plain sight, then the book, the character, the moment, the conflict doesn’t work. That’s what I tend to struggle with the most: A character that’s too in the know, that’s too open… It never works for me. I need a character who seems to be showing you their heart, but who is in fact in an enormous amount of pain or turmoil. I think that’s because I came from a very strict, authoritarian, military family, where everyone had a very strong mask and people had a habitus of ease, a habitus of joy, but a turbulent interiority.

It’s often said that great writers are also great readers. What book are you currently reading?

You young people don’t suffer from this yet, but when you get to be my age, your eyes start going weird, so for me it’s easier to read on my Kindle. It keeps a nice list of what I’m reading. I’m reading Emily Itami’s Fault Lines, and I’m also reading Catherine Hernandez’s Crosshairs, and the third book I’m reading – ‘cause I’m one of these people who has to endlessly read multiple books – is Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World. I’m enjoying all of them very much.

You know, everyone’s got their talents, we’ve all got some shit we’re pretty good at. I won’t lie, I’m a way better reader than I am a writer. In fact, if I was a worse reader, I would be a better writer. I’m always reading. My Kindle keeps track of it, I read a book every three or four days.

How do you deal with writer’s block?

I do get blocked very easily, I suffer from depression. Probably a bad idea, and I should not do this, but how I get through it is by reading. What I should do is write more, but instead I go over to the thing I love, but ultimately you should be writing. I think that’s my mistake. I joke with a friend of mine, and I always tell her that for every page that I’m stuck on, it feels like I have to read a book. One book, one page, a terrible exchange.

Do you have a comfort book?

Yes! Always. I think I read Watership Down at least once a year, the rabbit book. And this is not a comfort book – most people would call me insane for saying that – but I love Song of Solomon. It’s got very little by way of gentle comfort, Toni Morrison’s literature is the opposite of that, but for some reason it gives me a lot of hope and inspiration.

Some critics argue that male writers should abstain from writing about certain topics. Do you agree?

I mean, it sounds like the left-wing attempt to tap into this sort of strange orthodoxy around creativity. Listen, family, people can write whatever the fuck they wanna write about. That’s just the facts, and I know it breaks people’s hearts because they wish to control this, they wish to create a border, they wish to be gatekeepers, they wish to be in charge of the literary aduana, to be like “this is legitimate, this isn’t legitimate.” All this new policing, this border security around creativity… It’s very close to what you see in right-wing circles, where they wanna do the same damn thing.

Ultimately the idea is that, listen, anyone should write whatever the hell they want BUT that doesn’t mean that folks can’t speak back to you, that people can’t level their criticism or respond. It’s always been a weird thing for me. I always tell my students you cannot drive creativity underground. It just doesn’t work. Policing borders, I can promise you, never succeeds. Now, critical dialogue is far more enriching, I think, far more valuable, more productive. But that’s just me.

I know there are folks who are like, “No X should write Y.” Okay, cool, that’s your bag. But people are gonna do it! And it’s certainly far easier for us to develop muscles around critical dialogue. What happens when the human happens? And what’s the human? The human is “You’ve got rules? Fuck you, I’m gonna break your rules”. I mean, what planet do people live on that you think we’re gonna create a rule, a line in the sand, and human beings are not gonna immediately want to cross it? I don’t live on that planet.

I think a lot of these fantasies come out of a very weird, strange place. I’m much more of the school of, listen, man, people are gonna write and say some wild shit, and what we should be prepared to do is to dialogue in an elegant and insightful way.

Your writing, particularly Oscar Wao, is chock-full of niche sci-fi and fantasy references, and employs plenty of Spanglish slang, yet it still appeals to most readers. Why do you think that is?

One, I got lucky. I mean, with art, you gotta get lucky. I don’t care what anybody says, being talented is cool. It’s nice to be talented, but it’s even nicer to get lucky. I got lucky, the book worked in a certain way. I was trying to find a book that would allow me to push what I would consider, you know, baseline English, as far as I could push it and still make sense. Of course there was a lot of code-switching in Spanish, there was a lot of very esoteric nerdisms, a lot of shout-outs and call-outs that were rather cryptic, and I wanted to see how far I could push that and have it still be English, to have it still make sense for people, for characters to still work.

Part of the long challenge of that book was that it was a game, it was me trying to figure it out. Sometimes a page had too much Spanish, too much nerdy, and I’d have to cut it down; sometimes it was too little, and therefore didn’t feel challenging enough. That took a very long time. In the end, even though I wrote the book for eleven years, I never felt comfortable with it. I had to consciously go through every page.

Did you ever think of just giving up? Or writing a different story?

All the time! And every other story I tried to write sucked, so I would end up going back. I would say it was a less-than-fun experience. That book was not fun. I look back on it and sure, it was a very successful book, you could say it was a triumph, right? But, internally, it was not a triumph for me. I felt like I’d gotten slapped around for eleven years. That book was hard. I have friends of mine who write books and they’re like, “Oh my God, it was such a wonderful experience, I was transported, my characters were speaking to me, it was as if it was just coming out of me naturally.” I’m like damn, you are lucky. That was not the way it felt. It felt like a shelf fell on me.

I’ve had experiences where the book came far more naturally. My first book came very, very naturally. Drown was like [*clicks fingers*]. And also, the first third of this novel that I’m writing, it just blew out of me like boom.

Oscar Wao could not exist without one of the novel’s greatest villains, the real-life Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. History can inspire fiction, but does fiction influence history?

Without a question. I mean, my God, the way that certain texts continue to haunt our imaginations. The way they’ve enabled and have helped promote certain kinds of social and political behavior. I mean, look, we know very clearly how many writers in Latin America have turned around – you don’t need to be, like, a Mario Vargas Llosa, but how many have turned around and been like, “I’m gonna get involved in politics.” Certainly, our poetic tradition in Latin America has been entangled with a strong political engagement.

With that said, I often think the way that it happens tends to be more like Einstein’s spooky effect: it’s very hard to put a one-to-one basis of how art enables certain kinds of political activity or ideologies. But, that it does, I have no doubt. For me, it’s far easier to see the importance of literature in its absence and in its repression. The way that dictators and oppressive regimes, malignant political actors everywhere always have as their essential playbook the elimination, the containment and the destruction of literature.

I think art has always been threatening, no matter whether the political ideology is progressive or not. It’s no accident that the most progressive elements in our society tend to get into the biggest fights with artistic practices. I mean, all the wild conversations around, for example, comedians. Art is difficult, it’s naughty, it’s super transgressive, and it’s also profoundly contradictorily human. People need to say and hear wild shit, and that isn’t the safest thing, but it’s human beings.

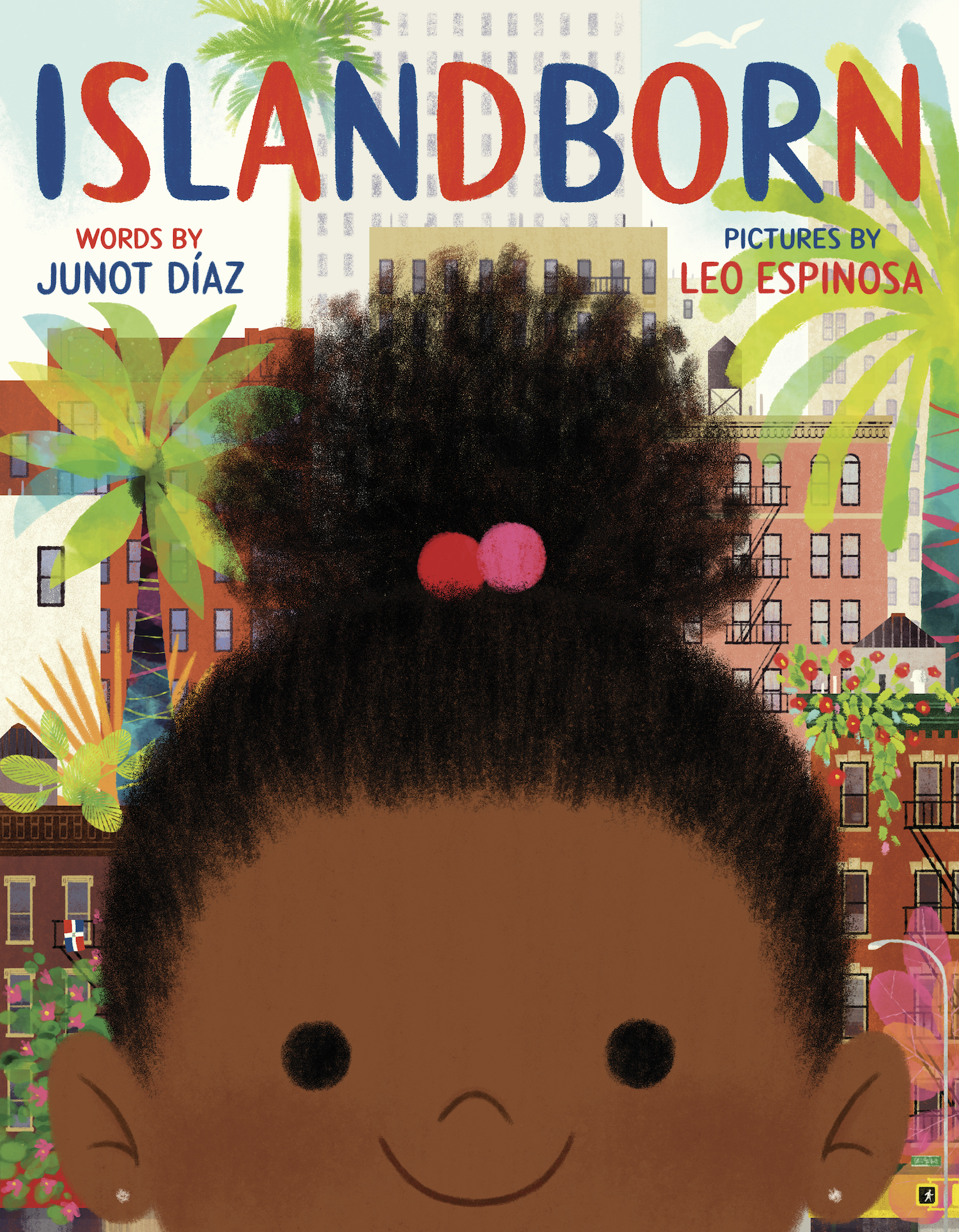

You published Islandborn, an illustrated children’s book. Is there truly such a thing as literature specifically for children?

Clearly our market has divided these things. We understand that there’s the consumption imperative, right? We slice up the market so it’s easier to sell to people. Stores convince people these genres exist. Often, a lot of books don’t even fit neatly in the genre, they’re just looking for shelf space. A lot of children’s literature as we know, the same with YA literature, is being consumed by adults! These lines are very, very fussy. Even when I was a kid, look, I was hyperlexic. I was an 8, 9 year old kid reading at a college level, so what was a kid’s book for me? Adult books. I don’t know.

Do you think we should protect children from reading about certain topics?

What child doesn’t need protection? I think that what isn’t being interrogated is who is really being protected. At any of these instances, when we’re dealing with gatekeeping books and gatekeeping art – it’s the adult sensibility that’s being protected. Because, I don’t know about you, but I can remember being far, far more mature, nuanced and far more experienced in the harsh reality of the world than adults ever gave me credit for.

Yo, I was always thinking, “Why are you protecting me from what I’m reading? Why aren’t you protecting me from the violence of neoliberal capital?” If a child needs protection, is it from a book or is it from our economic system? But, hey, I don’t have children, so to each parent their own. It’s tough, because, on the one hand, who doesn’t want their child to have a very “innocent” life, who doesn’t want to not see how much their child has already been exposed to?

You have written extensively about sense of place and the immigrant experience. What does “home” mean to you?

Oh my God, how awful of you to bring this up! In fact, I had a very long conversation today about this very, very topic. I lived in Mexico City for a year, in Rome for six months, I lived repeatedly in Japan, I’ve been there almost twenty times. I lived in Berlin, in Santo Domingo, and there is no doubt in my mind that losing my first home has put me in a perpetual search for a place that I can call home. I’m still looking.

I look at my siblings – I have two who landed in New Jersey and never left the state. They were like, “This is it, whatever happened to me in immigration, I don’t wanna move.” And then you have someone like me who can never sit still. I’ve had more new apartments than I can even count. I think whatever happened, for me, home is still something I aspire to. It’s probably because I miss what I lost. I miss my grandparents, I miss being normal. As a Dominican kid, I was normal. I grew up in a barrio where everybody looked like me, everybody was as broke as me, nothing was different. I long for that, I think. We never get back what we lost in childhood.

Do you see yourself in any of your characters?

I shouldn’t say it this way, but in general, when I came of age, I was always a person who found it a lot easier to admit, despite the kind of heteronormativity and hegemonic masculinity in which I was raised – I always found it a lot easier to admit that I was fearful or that I was weak. Part of that was because I had a very masculine family, a very masculine background. I think I’m drawn to a certain kind of anti-comemierdería. I think belonging to a Caribbean culture, to a Latin American culture, means that the politics of respectability are overwhelming. Comemierdería is our first language. There was so much posing, we always pose. I think my art is a reaction to that.

Could you explain what comemierdería is for our readers?

Politics of respectability, of appearance. Being known for something rather than being something. You haven’t read a book in your life, pero tú eres un todólogo, tú sabes todo (but you are a jack of all trades, you know everything). Astrophysics? You understand it. Your wife left you, you got fired and your dog bit you, and you’re like, “Pero yo estoy heavy, yo estoy bien, (I’m strong, I’m fine) everything’s great.” It’s constantly wearing a mask to try and make ourselves look better.

As a writer, I’m always drawn to the characters and the aspects of them that are weak, that fail, that are limited, unheroic. And then there’s another part of me who’s drawn to my characters who have enormous loyalty and integrity. I think my campesino abuelo (peasant grandfather) who raised me gave me a fever for loyalty that has served me well. So I’m drawn to characters who are often weak, cowardly, as I’m drawn to characters who have enormous loyalty, negative or positive.

Be honest: can an individual really be taught how to write? Can anyone become a writer?

I assume we all have an enormous capacity for storytelling. Whether we all wish to dedicate the time that it takes to get over our shortcomings and our inhibitions and our deficits, that’s another story. I know that if you add a modicum of motivation and a modicum of literary education, teaching a person to write is easy. Look, if you’ve got an okay ear, someone can teach you to play an instrument. It’s the conservatory model, it has worked for hundreds of years. You don’t have to be a genius to write a bestselling book.

On the other hand, the literary life is a very hard life. And that requires commitment that no one could teach. That comes from within. I can teach anyone the basics tools, but to stick to it… But I really believe it. I would not teach writing if I didn’t believe that I could train most people to be writers.

Is there anything you can’t teach?

Well, how could you teach anyone inspiration? How could you teach anyone to be more compassionate with themselves? What you can do is model it and hope they pick that up. Really, the beginning of any art is having a relationship with yourself that hopefully involves compassion. Now, are there plenty of artists who have no compassion? Yeah, no question. Do they drive themselves mad? Equally legitimate.

I think with literary arts, it’s far easier for you to do the work if you have some compassion. Can you do it without? Of course. Does it take four times more energy? Of course.

You’ve dealt with trauma in your life. Has writing ever served as a sort of therapy for you, or has it been a way to push it aside?

I definitely don’t think writing has been therapeutic. I would never say that yo boto el golpe (I’m releasing stress), right? I don’t think that is the case. I think I’m driven to write, but to heal, writing isn’t what helps me. For me, it’s been therapy, morning contemplation, connection. I could write all these books about these terrible things and still be completely broken inside. It’s never been catharsis. I get NO catharsis. In fact, I’m usually more depressed when I finish my books.

So in a way, even if reading is your sort of home, writing isn’t?

No. A friend of mine who passed a few years ago, one of the greatest Dominican artists, Tony Capellán, always said about his own work: “Listen, if somebody walked up to me right now and said, ‘I could take your talent away from you,’ I would give it up instantly, it’s such a fucking agony.” I’ve always resonated with that. But that’s never gonna happen, no one’s gonna take it away from you.

I have friends who are writers who are like, “I live for writing, I would die if I couldn’t write.” I’m like, yo, I think writing is gonna kill me! But it’s alright, some of us are called to arts that we find exquisitely difficult. That’s absolutely normal. I envy those people, diablos, wonderful.

[Photo at top: Nina Subin]

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.