British-born Ghanaian designer Kusheda Mensah is one of the most original and distinctive talents emerging from today’s furniture and industrial design scene. Having made her breakthrough to great acclaim shortly before the pandemic, she talks openly to AMEX Essentials about her aesthetic philosophy, what it means to be a woman working in the world of design, and the challenges of guiding her business through the difficulties of Covid, as well as sustainability, motherhood and more.

Picasso is often quoted as saying, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” How does that resonate with you as a designer?

Kusheda Mensah: Well, I think an artist and a designer are one and the same. If you breathe life into something through colour, through materials, through your vision and so on, you can be either one of these things. An artist or designer. Designers are artists, too.

It’s difficult to articulate, but the boldness of your designs seems to embody a sense of fun and playfulness. How deliberate is that? Do you have fun yourself and feel a sense of playfulness when you are working on new designs?

I think playfulness is inherently at the heart of my practice. It isn’t deliberate, but I think it’s a part of nature and comes out in my work. I always start designing for practicality, but end up with forms that fit the elements of functionality and look very playful.

You studied print design at the London College of Communication, what convinced you to make the jump from fabrics to furniture?

My final collection at uni gave me the confidence, actually. I always had a passion for print and texture as I was studying that course, and I wanted to translate that through form. Actually, it was more a test on how my prints would look on different forms.

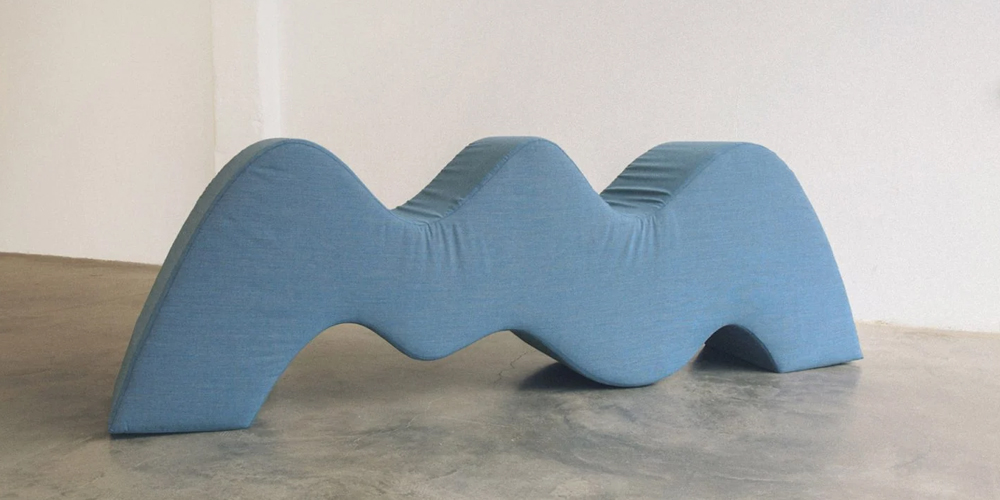

I used to print lots of bold forms, lines and shapes, both physical and digital. And so I used those abstract shapes to build a collection and used those same prints on suede to cover what I call a beta version of my Mutual collection, and used my final collection as a trial.

The final thing was displayed as a sculpture, more as an exhibition of prints than of form. At the time, it was an experiment of a concept I ended up exploring and executing, which brought me to this point.

Having arrived at that point, do you still retain a secret passion for print design? Can we ever expect to see Kusheda Mensah wallpapers or cushion covers in the future?

Oh, no secret at all! I love textiles and print. Fabric use informs my work, and I’m also Ghanaian and a lot of our fabrics have messaging in their print, and the colours of fabrics are allocated for occasional wear, so it’s in the framework of my being. I’m sure at some point I’ll expand and come back to what feels like home – for sure.

Having switched track on your chosen design path, and then found the courage to start your own business, do you think you are a natural risk-taker or was it a struggle to make those decisions?

Umm, it was kinda both.

I’ve always wanted to start my own business, but I have African parents. Period. If you know, you know.

They always wanted me to pick a sensible career path like doctor or lawyer. But I had another agenda and I had to be brave – not only to go against the grain, but also to constantly prove to them via accolades I received that my career was worth having. Plus then to risk owning and managing my own business despite an [initial lack of] business acumen. I had to show them it’s all been worth it. And it has. So maybe I am a natural risk-taker because I guess I didn’t care whether I failed, and luckily I haven’t.

How difficult is it as a young furniture designer to find one’s path, when so much has been done in the past by celebrated icons of design? Do you ever feel that weight of design history, or do you embrace the challenge of breaking barriers and doing something different?

I was always taught to never compare myself to anyone. I’m one of one, so whatever I do feels one of one and the first of its kind. Because I did it. But, of course, I feel pressure to make a dent in design history.

Questions like, “Am I making history in this sector as a Black female designer” or “Am I inspiring others?” Other questions arise like, “Am I making a dent in history?” or “Am I being sustainable enough?” [These matter] because I would like to. I have children, so to have them see me as an example is a great vision of mine.

I am also aware that there is a great pressure, being Black and female, to create a legacy and reputation that other young women can follow as a blueprint. This has a great weight when there aren’t many of you in an industry. Especially in what is predominantly a white and male industry, there’s an enormous pressure not to let people down – so that others don’t have to think about that when they go into this industry. They will be able to just create and do what they love.

In the end, I try to do the same and focus on my love of the practice and hope that will pave the success I aspire to, and that it will also inspire others.

We seem to live in an age of virtual communities where, despite those virtual connections, many people have actually become increasingly isolated. That was probably also exacerbated by the strange experience of the pandemic.

Your designs seem to directly address that: your work features bold ergonomic shapes that can be moved and assembled or reassembled to encourage greater interaction. Do you see that as a hallmark of your work and something you want to continue pursuing?

Yes, that’s something I definitely want to continue pursuing. Essentially, at the heart of my practice is people, so however I can focus on helping others to interact, I’ll need to keep pursuing, and to focus my work on encouraging interaction between others. As you rightly said, people definitely are becoming more isolated, so as a designer it’s my job to problem solve and come up with ideas that stand in line with my design focus on togetherness, and bring that to life.

When I started my practice and created the Mutual collection, it was a conceptual idea that bold forms made in modular shapes could bring people together. But it worked, it’s very artsy in its thinking, but still worth pursuing.

The originality of your work caught the attention of the design community immediately, with a wave of enthusiastic coverage. It must have been difficult to maintain that momentum with the unexpected arrival of the pandemic. How tough was the pandemic for you, and what have you learned about yourself from that experience?

Oh, super tough. I suddenly had to stop and think about my purpose within the industry. I also worked for a lot of brands doing unpaid work because projects never came to pass due to the uncertainty of the virus, and I felt devalued.

I had a few funding opportunities that validated my presence in design, and the funding at the time kept my small business afloat.

I also had my premature son during the pandemic; he was born at 24 weeks, so extremely small. He was extremely sick and had lots of surgeries, and when life comes to a head and you are looking death in the face, nothing else seems quite as important.

I was still working whilst my son was in hospital and wasn’t able to see anyone, so what I’ve learned is that I’m extremely strong and resilient and can truly work in any climate.

It was definitely hard on my mental health, but I also had the space and time to plan what the next steps business-wise could be for me.

Despite that strength and resilience, do you ever hit a creative dry spell as a designer? A period where the ideas just don’t come as quickly as you’d like?

For me, definitely. Especially if you are going through a difficult time, as I mentioned. I wasn’t feeling particularly inspired, but I find travel, talks and exhibitions all help me stay inspired.

I’d say the number one thing, though, is speaking to other creative friends. Speaking to them whilst you’re in a lull, and hearing their fresh perspective about what you could do. One of my favourite things to do is to reach out to creative people I don’t know particularly well. They may or may not respond, but if I have a question then I will message them and hopefully hear back about what they did or are doing to get through to the other side. It always puts a battery in my back. People’s experiences and stories are so powerful to me.

Is sustainability a central factor in your design ethos, and do you worry about the world we are leaving for future generations?

Absolutely. Which is why I don’t make something if I don’t think it’s meaningful or contributing to society. I love my practice and my focus on encouraging better social behaviours, but does that mean every idea I have needs to be made at mass or needs to be made period? I personally don’t think so.

I guess I pick design that I believe in, and that stays true to my focus, and produce that. Or work with brands and companies with a sustainable focus. We’re all still mapping this out. The design industry is quite wasteful, so I’m navigating that constantly – especially as a small business. I always want to stay responsible, even though it’s costly.

Has parenthood changed your approach to design, or affected how you envisage developing your studio and way of working?

No, not particularly. I think I defo have more and more of a sustainable focus though. Thinking about the kind of world they’ll live in drives me to create better and more sustainable design.

In 2022, your name and work was added to the Design and Technology curriculum for GCSE students in the UK, alongside 11 other diverse names such as Zaha Hadid, David Adjaye, Rei Kawakubo, Karim Rashid and Morag Myerscough. That was well-deserved, but must still have been incredibly exciting and a wonderful surprise, so we get it if you’re still celebrating.

Has that recognition fully sunk in yet? Does it give you a greater sense of responsibility as a role model? And does it give you even greater determination to continue pursuing your chosen path as a furniture designer?

You know, one of my goals when I first started this journey was just this.

I used to sit in my textiles class and look at the names I would study and think, imagine if my name was in this. So when I had the privilege to be alongside the names you’ve mentioned, it was an incredible honour. My career has just started, to be honest. So to stand next to great people I admire… I was incredibly honoured.

It has certainly sunk in, as I do not want to take it for granted. One day my kids will see my name in these books, and I have to keep my/their legacy going. Which is a greater sense of responsibility, but not one I didn’t [already] have for myself. I thought and dreamed it, and have now achieved this thing, and must keep pursuing my dreams.

Maybe it sounds corny, but if you really dream and believe it, you can achieve it. Clearly!

Finally, what can we expect next from your studio, and how do you envisage your work developing in the future?

More works that you can buy and have at home and invest in yourself for your future. What I mean by that is that you will never want to throw it away. I am so excited about more distribution, although I can’t really talk about it right now…

I’m also looking forward to more group shows in galleries, and working more with galleries.

Discover more about Kusheda Mensah at her website.

[Photo Credit: Images courtesy of Frank Lebon/Kusheda Mensah]

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.