For a graphic designer, Dr Kate McLean spends a lot of time sniffing around.

That’s because the UK-based researcher, artist and smell archivist has spent the last decade experiencing the world through her nose: observing, documenting and interpreting the perfumes and odours that combine to form a city’s unique olfactory fingerprint.

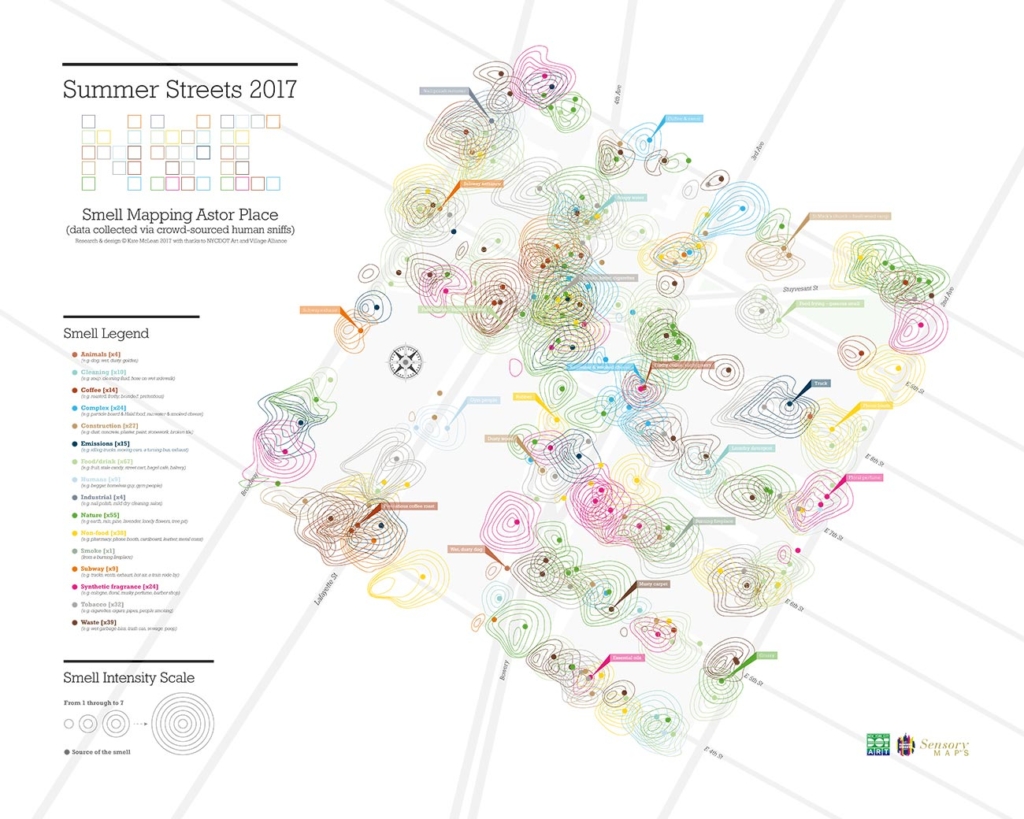

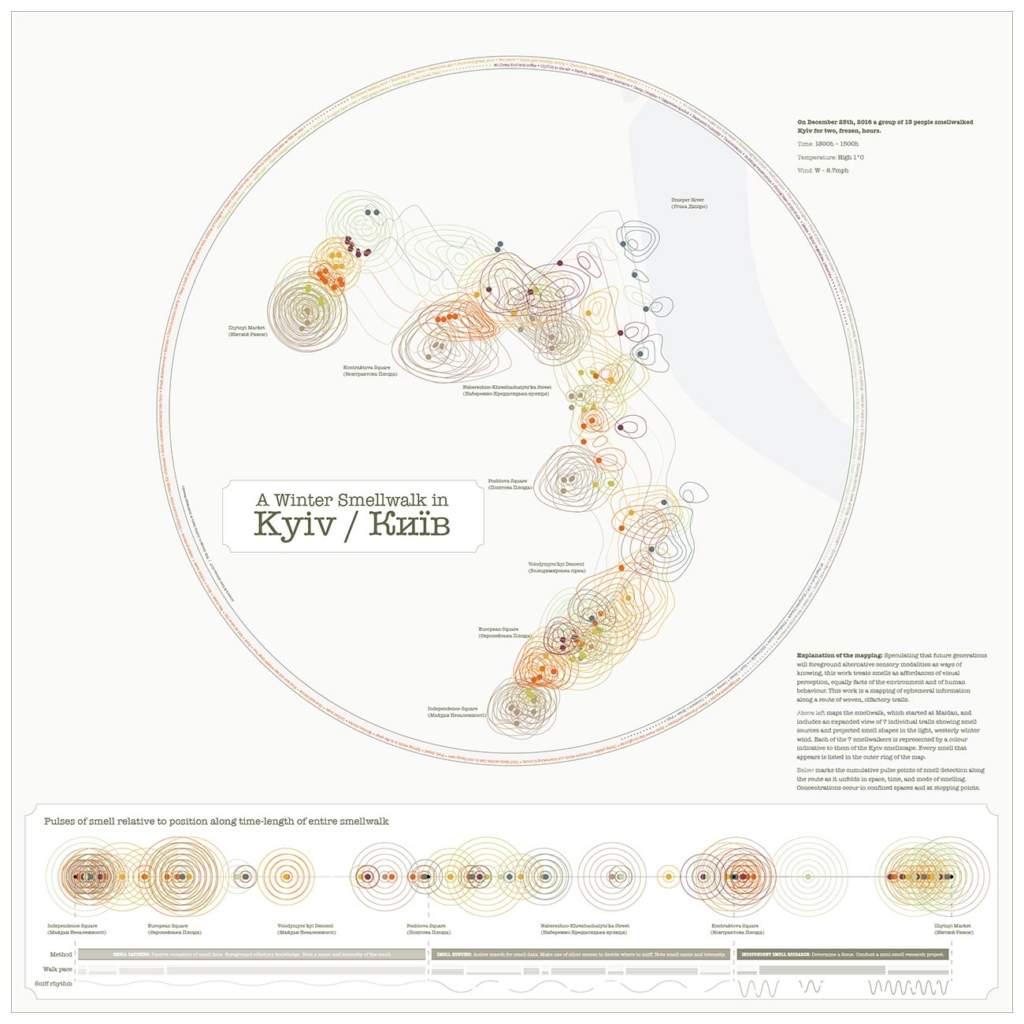

Combining her own findings with the scent observations and interpretations of locals who join her guided smellwalks, McLean has created a series of smellmaps – beautiful visual translations of the perceived ‘smellscape’ in a given place. From Singapore to New York City, Milan to Marseille, McLean’s sensory maps can reveal more about a place than normally meets the eye. Aromas of exotic spices wafting from apartment blocks might indicate a community’s diverse makeup. Musty odours can hint at disuse and neglect, while sudden floral and botanical notes may signal that you’re entering a well-landscaped, affluent area. Indeed, there’s much to be learned by simply following your nose.

We asked McLean to share some of her insights into smellmapping, as well as how tuning into our sense of smell can allow us to experience our own home town in new and surprising ways.

Amex Essentials: For the uninitiated, what is a smellscape?

Dr Kate McLean: The smellscape is the olfactory equivalent of a visual landscape. The smellscape can be witnessed individually by a person at a moment in time, or it can be collectively encountered and shared by a number of people together, making for a more varied range of smells.

What made you begin thinking about exploring and mapping a city through its scents?

I started mapping places through smell in 2010 when I was studying for an MFA in Graphic Design at Edinburgh College of Art. The city was new to me, and I started the course considering ways in which design might be ‘re-physicalised’. I was always interested in cartography, so I combined the sense of touch and mapping to produce a tactile map of the descriptors ascribed to the city’s various neighbourhoods.

One day, with an exhibition forthcoming, I simply swapped senses and ‘mapped’ Paris by its smells. In this first smellmap, I created replica ’smells’ in my kitchen and put them into perfume bottles and apothecary jars, and invited the attendees to sniff each jar and then write an emotion and a location that they associated with the smell.

Our sense of smell is a powerful tool for perceiving the world, closely linked to memory and emotion, yet we often overlook it – failing to really acknowledge smells unless they’re strong or unpleasant. Why do you think that is?

I think we take our sense of smell for granted in a similar way that we take our little finger or little toe for granted; all operate in conjunction with other parts of the body to provide balance, but it is only when they are damaged or missing that we notice just how important a part they play. Unlike many other mammals, smell is not a primary human sense: our accepted knowledge of the world derives from sight, but smell rounds out the experiences of what we see. It adds detail to the full picture, but rarely do we rely on it alone – except as you say when we are sniffing milk or fish to detect if it is safe or desirable to consume!

Based on your experience and research, what can we learn by more actively tuning into our olfactory sense? Can it change the way we ‘see’ familiar places?

We can learn much from temporarily deploying smell as a primary sense of knowing. Firstly, it is incredible to realise just how many smells we can detect and name. Secondly, we learn that, despite their ephemeral nature, we experience smells not just as simple objects but as having differing characteristics of duration, intensity, ‘colour’ and even ’shape’. And finally, we move more slowly through familiar neighbourhoods, noticing parts of it that we may have previously passed by.

In cities you’re studying, you lead locals on smellwalks that function as a method of collecting data for your sensory maps. Of course, different people often report different scents in the same place. How do you reconcile the various responses from smellwalkers?

All of my maps are based on local inhabitant perceptions collected through smellwalks; it is the fundamental principle behind the work that those in situ are best placed to understand and name the olfactory dimensions of their immediate environment. Of course not everyone agrees [about what they’re smelling], and depending on the scale of the project and the number of smellwalkers, I have generated a number of methodologies to deal with the contested nature of the smellscape.

The process starts with me manually transcribing the smellwalker data into a database and looking for patterns and commonalities. After that, I might either choose the most common smell in a given neighbourhood and check for reference to it in other parts of the city – as in ‘Scentscape Singapore’ – or map individual perceptions in specific streets to illustrate the differences as in ‘A Winter Smellwalk in Kyiv’. These olfactory discrepancies might derive from a number of variables: the relative height from the ground of individual noses, airflow and wind patterns that distribute smells, or the exact moment of the smell detection.

What are the most unusual or evocative scents that smellwalkers have reported?

Some of the more unusual smell descriptors featured in my smellmaps include “smell of shattered dreams”, “broccoli / deep dark secrets” and “a hard life” – these are all complex odours combining several discrete elements in one sniff. A couple of smells encountered during smellwalks that I find very evocative are “smell of local government” and “moments of joy” – the former was inside a municipal building and the latter was referring to cigarette butts, but the sniffer imagined the pleasure given to the smoker by the experience.

Generally speaking, what do smell maps reveal about a city? Can they be used to help communities improve overall quality of life?

Smell maps facilitate discussion and awareness of the smellscape, they reveal how the small and overlooked aspects of your cities have meaning to many and therefore have potential to help communities improve their overall quality of life. I think that, with lockdown, many people living in cities without access to green space realised just how important such areas of respite and refuge are from the smells of a built environment.

This summer, with holidays cancelled and travel plans on hiatus, many of us are looking to explore familiar places in new ways. What tips do you have for anyone looking to better experience their hometown through their nose?

Undertaking a smellwalk is a great way to rediscover familiar environments. The Smellfie Kit that I developed gives a background and a recording grid for a smellwalk, but you can use ordinary paper. You can smell anywhere, but limit yourself to 45 minutes and no more than two kilometres. Start by sniffing the air, then get close up to objects that look or sound interesting, then compare the smells of four objects that look the same. Warm and humid conditions are optimal, but you can do a smellwalk at any time.

What would you say is your favourite place in the world, and what are its defining scents?

I don’t have favourites (which makes creating passwords really problematic for me!), but my current favourite place is where I live: a small coastal town in the Southeast of England. Its defining scents change on a daily basis depending on wind direction, but they include salty air, seaweed, tar, lavender, fig tree, oysters and doughnuts.

What smellscape-related projects do you currently have in the works?

I was working on a Smellscaper app that went through two rounds of trials and testing – it was an element in my PhD, and was a part of a research bid I put together for a research position last year. Unfortunately I was not successful, but I would still love to develop the app further – though as with all things like this, it needs funding. There are already apps for smell detection – usually for reporting smells – but what I am proposing is to link the smellwalk and smell detections with an algorithm to generate instant smellmaps so we could compare cities in different parts of the world synchronously.

If there are any academics out there interested in co-writing a research bid, or indeed funders looking to support sci-art projects, then please do get in touch with me.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.